US Economic Policy Moves From Abstractions To Reality

US national security advisor, Jake Sullivan, gave a speech a few months ago that signaled a major shift in Western economic thinking.

He started by critiquing the dogma of the last few decades:

There was one assumption at the heart of all of this policy: that markets always allocate capital productively and efficiently—no matter what our competitors did, no matter how big our shared challenges grew, and no matter how many guardrails we took down.

Now, no one—certainly not me—is discounting the power of markets. But in the name of oversimplified market efficiency, entire supply chains of strategic goods—along with the industries and jobs that made them—moved overseas. And the postulate that deep trade liberalization would help America export goods, not jobs and capacity, was a promise made but not kept.

Another embedded assumption was that the type of growth did not matter. All growth was good growth. So, various reforms combined and came together to privilege some sectors of the economy, like finance, while other essential sectors, like semiconductors and infrastructure, atrophied. Our industrial capacity—which is crucial to any country’s ability to continue to innovate—took a real hit.

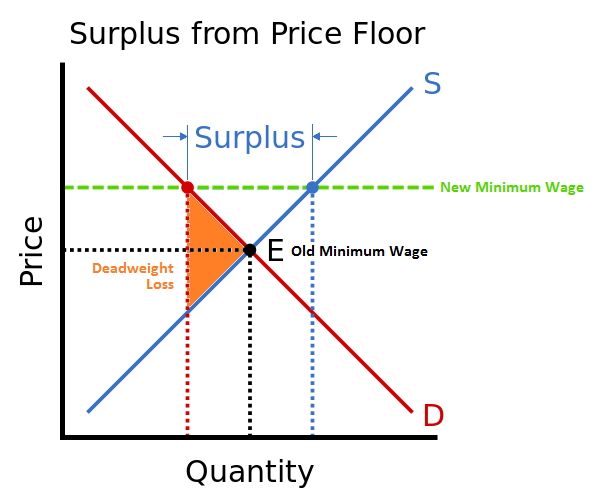

In public high school, every American is taught this graph:

I was told the entire science of economics rested upon this graph. If you look at neoliberal think tanks like the Cato institute, you will find this graph still serves as the foundation for many of their ideas.

A neoclassical economist, arguing from such a graph, might say that minimum wages are bad because they create "dead weight" in the labour market.

All the red stuff in that graph? To the neoliberal, that is PURE loss. To not operate in equilibrium is absolutely irrational. It's needlessly "inefficient", because now you (theoretically) have workers who want to work for less, but can't, because of that pesky minimum wage. And you have employers who would create jobs if wages were lower, but now won't. And so we are all worse off!

Of course, this is terrible reasoning. First, there is no consideration of the actual societal outcome. The labor market is asymmetrical. In the absence of worker coordination, employers have much more bargaining power than employees. Many workers do not want to work for less, but can be forced to, by poor economic regulation, in order to survive. Many employers do not necessarily need to hire at lower wages, but given the option, they will. The only thing “optimized” when optimizing a supply-demand graph is the efficiency of mutual exploitation. There is no sense of the human being on either side of the transaction.

What are the actual products people are building in this country? What kind of lives are they living? Is it sustainable? These questions are totally ignored by the neoclassical economist.

The new economic thinking, Sullivan says, satisfies people, not models. No more "tariffs create inefficiencies", but:

Asking what our trade policy is now—narrowly framed as plans to reduce tariffs further—is simply the wrong question. The right question is: how does trade fit into our international economic policy, and what problems is it seeking to solve?

Our international economic policy has to adapt to the world as it is, so we can build the world that we want.

Strategic Industries

Part of this new realism is industrial strategy. A key industrial strategy is to get rid of big economic dependencies:

ignoring economic dependencies that had built up over the decades of liberalization had become really perilous—from energy uncertainty in Europe to supply-chain vulnerabilities in medical equipment, semiconductors, and critical minerals. These were the kinds of dependencies that could be exploited for economic or geopolitical leverage.

consider critical minerals—the backbone of the clean-energy future. Today, the United States produces only 4 percent of the lithium, 13 percent of the cobalt, 0 percent of the nickel, and 0 percent of the graphite required to meet current demand for electric vehicles. Meanwhile, more than 80 percent of critical minerals are processed by one country, China.

(India is in a similar situation with minerals, getting ALL of its potassium through imports. This is worse than being dependent on lithium or graphite, because, without potassium, we can't grow food. India uses millions tons of potassium a year for agricultural fertilizer.)

Free trade dogma would say eliminating dependencies is "inefficient", because now you're paying more to produce a good that you could import for less! Save the money on the import, and use that money to invest in the industries you're good at! Why re-invent the wheel?

Ok, India and China have frequent border disputes. What if China said to India, "if you don't redraw your border, we're going to cut you off from our electronics?"

The free trader might say, well, this is an excellent opportunity for another producer to fill this need! Again, they are forgetting reality. China's electronics exports to India is 30 billion a year. What country is going to immediately start churning out an extra $30B of electronics for export?

For a small country like Singapore to have such dependencies is fine. Trusting that there will always be sellers for your demand might work. But for a large country like the US and India, these large dependencies are short-sighted.

You could maybe make an argument like "China needs India's market just as much as India need their electronics", but that's a hand-waivy bet on how people make decisions, which is unsound, especially when the risks are so high.